Q4 2024 round-up

This won’t take long. Film and I aren’t really speaking at the moment.

Only the River Flows (2023, dir: Wei Shujun)

Low-key Chinese detective film that isn’t a neo-noir but is a 90s period piece. I don’t see what the 90s styling specifically adds here; is it an excuse to shoot this in a moody 16mm? If so, bravo.

Things pick up for lead cop here when his field office is relocated to an abandoned cinema and he begins to fancy himself the protagonist in his own drama: the crime is never solved because he develops hunches that something else is afoot, which ends up drawing a wider net of innocent people in toward their doom. The art-house flourishes of dreams and Twin Peaks style mystical utterances wear their welcome, but they’re just a small part of a well-constructed drama.

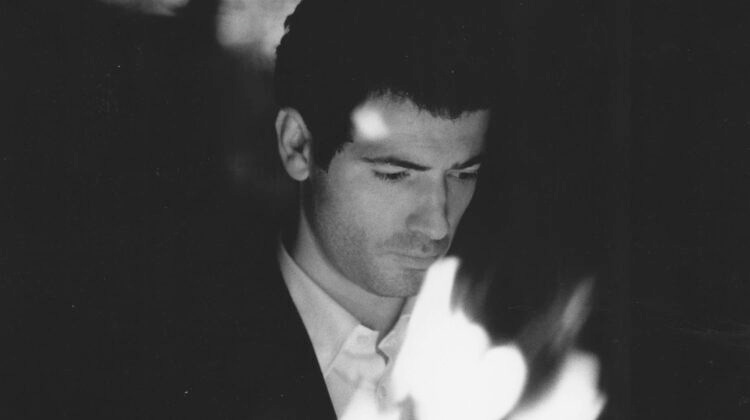

In Praise of Love (2001, dir: Jean-Luc Godard)

The post-Histoire(s) du Cinéma style of Godard appeals to me: pitched between drama and document, traditional narrative and cinematic metacomment, political and personal, enigma and banality. A man is working on a project (exactly what, we never learn) on the subject of couples and love, and a Hollywood company is attempting to option a story about love during the Nazi occupation and Holocaust. So really - it’s about cinema and its position in the ongoing tumult of the 20th century (for Godard the 90s was not about peace; Sarajevo occupies his mind constantly), turning ultimate feelings and expressions into banal consumable images.

Style-wise, the first 58 minutes looks like prestige art-house:

Then, after some black leader and voices talking in the darkness, we move into the past with heavily saturated digital video:

This didn’t quite run a knife through me like Notre musique did, but there’s a section where someone is talking about the difference between death in a tragedy vs. death in melodrama that is, to me, a worthy addition of the great aesthetics debate of the 20th century as evoked in this book.

The Past is a Grotesque Animal (2014, dir: Jeff Miller)

The past is a grotesque animal / And in its eye you see / How completely wrong / you can be

Documentary about the long-running indie outfit Of Montreal and its dictator Kevin Barnes. They’re a unique lot, whatever you think of their aesthetic, but this film leans into the lead creator-as-tyrant mode. Kevin Barnes is too pass-agg to really come over in the same way as say Anton Newcombe, but he does trip himself up a couple of times in a film that is doing its level best to sell his band’s story back to the fans who already know it.

The main issues are that, as a fan-made hagiography, it expects you to intuit why this group is meaningful (I like them and I’m not sure exactly why: it would be cool if someone could contextualise what they do a little) and it is afraid to touch directly on some of the main issues such as Barnes’ race-play alter-ego Georgie Fruit. Barnes would apologise for this 6 years later, but I don’t think the world changed so much that people didn’t realise it was fucking weird at the time. Even I did and I am really not very bright.

There are some touches that hint at issues, notably the tight conspiratorial way that Barnes and a young female addition to the group are shot and edited around an increasingly grumpy long-suffering band. On the whole it doesn’t make for an essential rock doc, but I ask you what exactly is these days?

nothing, except everything. (2023, dir: Wesley Wang)

This 13 minute short film that has been optioned by Sony for conversion to feature will make its director the youngest to helm a major studio film at 20, beating out Orson Welles by a good half-decade.

n, ee is an interesting case study, I suppose, in trying to examine what appears meaningful to people whose brains have been affected by daily social media use: extremely obvious and trite expressions, random grabs of thinkers (epigrams from Marx and Jung that turn their words into sigma #grindset nonsense) and some cod-philosophising cosmic mumbo-jumbo about the significance of the number 7. All of this gives way in the end to some tedious pablum about living life to the max.

Technically, despite arbitrary use of various approaches, it is constructed at a high level. It chiefly draws from aesthetics of music video and social media rather than anything previously of ‘serious’ cinema. But who knows? Maybe the ‘cinematic’ of 50 years time is not going to be like the cinematic of 50 years ago.

I watched this because some of my students were up in arms about it, given that Wang is essentially a rich guy with nothing to say taking a spot that someone interesting might use. As uncharitable as that might seem, I’m inclined to agree.

But I don’t think the presence of bad art is a block to good: if anything, it should be a spur. What it is it in this that you do not like? Congratulations, you may have found where your own heart is.

The Substance (2024, dir: Coralie Fargeat)

Spurned by a cash-only football turnstile I decided to roll into the nearest cinema to see whatever was playing. As chance would have it, it was the film that half of the people I knew had seen and had ‘opinions’ on.

Seconds after seeing it, I wasn’t sure I liked it. Then a few days later things had rolled around in my head a lot and I found that beneath the tidal wave of Things Happening in a generally straightforward conceit, there were glances and looks and gazes that contained more.

Not the obvious Verhoeven-esque media satire and flirting-with-being-pornography-itself critique of sexualisation, but tiny things like the young version glancing at the armchair that the old version had sat in for a week, aghast that someone would live in their own space and not treat it like an Instagram heterotopia.

Demi Moore’s recent Golden Globes speech slightly soured me (pity the successful actor with $200m in the bank who wasn’t considered a serious actor but had a very good career) but that’s awards ceremonies I guess: barometers of dead politics. All the same, it takes a fair bit for me to get on board with horror that is horror-and-proud (being an inveterate snob) but this one gets the YWTTWY stamp of approval.

The Room Next Door (2024, dir: Pedro Almodovar)

Swing-and-a-miss for the master. Old man Pedro has been circling death in his calendar for a few years now - but in this one he seems to face it head on. Tilda Swinton plays a dying war photographer, Julianne Moore an estranged friend who writes about death, and together they experience a slightly brittle but occasionally touching last few weeks together in a Grand Designs property.

Little story threads are seeded and you wonder when, in classic Almo style, it's all going to start clicking together and going gently nutso. John Turturro plays an ex-lover of both who warns Moore that she'll need a lawyer if she's in the house with a dead woman and the police do investigate and think she knew about the suicide, which she did, but the lawyer sorts it all out and it takes 3 mins max and it is like what is point?

On reflection TRND is a tone poem about facing death and remembering life and art. But he's done that before, and also wrapped great stories around it laced with indelible moments. There's none of that here: just slightly clunking art references and an emotional relationship that never quite gels. The best bit is when they're watching someone else's film.

It's not bad, I don't think he could ever be bad, but it is ever-so-slightly mediocre. Part of the problem here is what registers in Spanish as camp and knowing comes across in English as expository overkill. Shame.

Dahomey (2024, dir: Mati Diop)

I’ve enjoyed Diop’s previous works but I thought this was largely phony garbage aimed at students and academics of post-colonialism and those crippled with liberal guilt. A number of articles looted by the French empire are returned to Benin. We see the figures being moved and reinstalled. The main object ‘speaks’ in a really embarrassing voice. The best bit is a university debate between some really interesting and forthright students but it feels hard to credit Diop for that.

Anora (2024, dir: Sean Baker)

Sex work is work, most of us agree, but even films that believe this often find it exceptional and difficult to put into some kind of overall landscape. One of many great things Anora does is put sex work into a modern framework: precarity. Maybe other films have done this too, but I haven't seen those. You could argue those bawdy musicals pre-Code like Gold Diggers kind of did this too. Anyway.

At first watch you might think Anora treats the subject with the same kind of exotic 'sex is hedonism' vibe other films operate with; however, beyond the fact that Ani doesn't hate herself and there's quite a bit of fucking, there's glimpses of the ordinariness: the shitty undesirable houseshare, the blocking of workplace benefits, the competitiveness even within, and partly because of, the job, etc. I can relate!

Last year I wrote about the 2019 film Bait in terms of precarity and the idea, albeit one that supports a slightly magical narrative device, that there may be a 'precariat consciousness' where people who are hanging on the crevices of the job market can "see" each other despite differences in gender/age/experience, whereas those with reasonable security seem to repress them into invisibility.

The relationship that develops in the back half of the film between Igor and Ani, though it partially conflates with romance, might also relate to this idea.

From the perspective of these oligarchical pricks, one is a hired fuck and the other is hired muscle; both are disposable. He can see her for her situation; she can't see him for his at first because he's been used by power to cement her lack of it. If they weren't so comfortable, the two Armenian middle manager types would see it too.

Eventually she begins to see him less as a 'gopnik' (flattening him into structure) and as someone whose role belies a dimension not useful for his job (just like Ani with her belief in actual love).

But this moment of recognition clearly unlocks pain that has been repressed throughout the film with small asides - speaking Russian seems to reflect some hidden past, mentions of grandparents but not parents, a generally atomised life to the point where Ivan's (quite literal) security seems incredibly appealing.

When you've lived like this for a long time, and someone truly sees you beyond your value as a body producing surplus value, it should be liberating. In reality it is very hard to accept.

The final scene felt very real to me, in all of its various positions and ambiguities. Igor and Ani could go on to marry and have the fairytale each wants, or they might never be able to unpoison their own minds from the horrors they've experienced.

What Doesn’t Kill Me (2016, dir: Sean Stuckey)

Legendary songwriter Vic Chesnutt gets appropriately-toned (ie. a bit sad) documentary seven years after his suicide. Doesn’t sidestep his awkward personality whilst celebrating his understated and underrated music (despite his occasional brushes with success). Probably for fans only though.

Phase IV (1974, dir: Saul Bass)

This is the favourite film of a friend and indeed it was said friend coaxing me into watching this in an Airbnb in Birmingham (long story). This was great!

Disregarding their interspecies rifts and bonding together, ants become very powerful in a way that is uncovered by two scientists billeted in half a Crystal Dome from The Crystal Maze. It doesn’t need much plot as Bass - famed for his Hitchcock intros - is really strong visualist, interspersing gnarly documentary images of ants around the sharp and minimalist action. Best seen with the wig-flipping alternate ending too, in which the liberation of being ruled by antkind is explored in an incredibly inventive way.

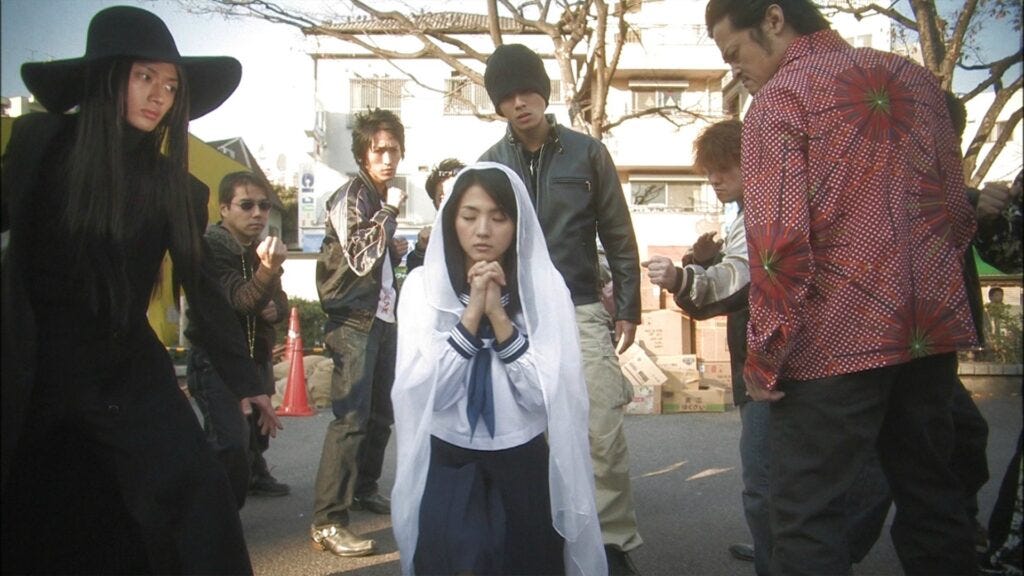

Love Exposure (2008, dir: Sion Sono)

A site that I check in on has this as the second best film of the 2000s so I thought I should give all TWO HUNDRED AND THIRTY SEVEN MINUTES of it a go.

It’s not the second best film of the 00s but it is pretty good and very entertaining for a film that long. It’s a completely cracked madcap satire, arthouse exploitation and pisstake of sentimental/'love narratives. Some of this feels like I’d need a Ph.D in Living in Japan along with 10 years of additional fieldwork to understand, but it might be worth a go.